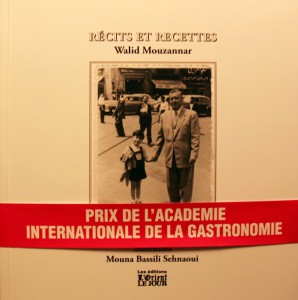

Even a cookbook can tell you a great deal about Lebanese society. This weekend I was at my father-in-law’s maternal cousin’s husband’s book signing in Sursock. (That sentence of course would just slip off the tongue in Arabic.) The book comprises two main parts, the first half being personal anecdotes, traditions and family tales and the second being recipes.

What I didn’t expect to find was an index at the end dedicated solely to names of people mentioned in the book. On a double-page spread all the surnames which appear in the book are listed alphabetically next to the relevant page (or pages for a happy few).

Now most people aspire to some kind of fame, especially in a small community where fame is easier to achieve and always seems to be almost within reach.

I remember a writer from the local gazette of the small town I grew up in pointing out that for every local person mentioned in the paper because they caught a large fish, won a dog show, or broke their leg, equated to several more sales to family and friends wanting to see for themselves the name in the paper. They get their fifteen minutes of fame, and they also get a feeling of belonging, of proximity with the publication or product.

The same is true of a cookery book. There is no shortage of recipes, always available from older female relatives, as Lebanese families really do know how to cook (with the possible exception of the latest generation with its penchant for takeaway from Western-style chains). But people will always be interested in a contemporary’s perception of shared experiences. And an author’s primary audience, like any Lebanese businessman’s network, is his family and social circle. So by writing about encounters with the characters who have passed his life, an author ensures an interesting read for this circle.

This has a ripple effect. These circles are not only particularly broad in Lebanon, they are also quite vociferous about homegrown talents they may have some connection with (a case in point: my father-in-law has told more Lebanese people about this blog than I have). Convince your nearest and dearest and you have an army of ready ambassadors who will naturally drop your product into conversation with all and sundry.

Of course, these are basic principles inherent to business, and companies in Europe have artificially recreated this in a form consistent with our more detached societies, offering advantages to some consumers willing to be “brand ambassadors” within their social group.

But including an index so one can browse the book with the sole purpose of seeing which names were dropped and in what context goes a step further. It puts the importance of those mentioned on par with that of the recipes, which are the object of the second index. Then again, that is the point of a book which is only half recipes, the other half being devoted to more personal musings and dedications to friends and family. It seems that the marketing was a success, especially if the turnout yesterday is anything to go by.

Perhaps the lesson is that food may be important, but people will always come first. The same pattern emerges from first meetings. Most Lebanese will first ask your surname and work through anyone they’ve known by that surname until you find someone you know in common. Often enough they find related kin, such is their persistence. Your location in the very small Lebanese family orchard will usually have been established before moving on to dinner. In time, two people close enough to have shared many meals can say that there is bread and salt between them.

Another very Lebanese element in the tone of the book which merits a mention is the pervasive nostalgia, characteristic of this author’s generation, that knew and loved a past Lebanon, the one that ended with the civil war and the advent of adulthood.

So if you have Lebanese family and you want to know if they made the grade and got their name published, check it out in Walid Mouzannar’s Récits et Recettes. And if not you are bound to find a delicious dish to rustle up for dinner.

Any association with the author or publisher has been disclosed. In detail, for the Lebanese out there.

I loved reading this. I think I might have to pick up a copy of the book. I have a Lebanese cookbook, but it isn’t any good. I have to rework almost everything in it.

Happy Holidays!